Common sense (or rather economic sense) would expect that excessive use of the printing press, especially in the US and Japan, causes inflation – if not hyperinflation given the amount of money injected into the system. And yet, it’s nothing of the kind. Are deflation and the printing press conniving in the US ? Or in Europe ? How can that be possible ?

The US has a base money supply (M0) issued by its central bank, which has exploded since 2008, with the well-known Fed injections and the three events of Quantitative Easing, QE1, QE2 and QE3, the last slowing somewhat in 2014 with Tapering, but still inflating M0. Normally, when base money supply explodes locally, it stimulates bank offered credit which facilitates investment, to the extent of overheating the economy and creating inflation, even hyperinflation, which is just the opposite of deflation. In fact, deflation is characterized by falling prices, through lack of demand (weakness in buying power) or because of oversupply (industrial overcapacity), or because of the two combined. Of course, deflation is analyzed on prices overall and not on a single sector in particular, because there are always several reasons that a specific sector is in brief restructuring, without plunging the whole of the economy into deflation.

According to classical monetary theory, inflation equals the difference between the growth in the money supply, M0, and GDP growth[1]. Therefore, the remedy in the case of deflation with a lack of growth is therefore just M0 monetary production, like the Fed with QE for example. But then, if it’s this specific remedy for the deflation which is being applied, it’s because the Fed’s doctor has diagnosed this illness in the US ! This is the first irrefutable admission !

We must, therefore, return to the fundamentals of the origin of credit and bank money to track down this post traumatic 2010-2015 period’s very special monetary characteristics, apparently of a deflationist character.

The central bank acts as a shareholder and provides capital to the bank, which it places on the liabilities side of its balance sheet. This is the bank’s debt to its shareholder. In return, the bank will be able to develop products such as loans, cash advances and financial services, to name but a few, which will be accounted for as assets on its balance sheet.

The entire capital provided by the central bank makes up what we call the base currency (M0 in the Anglo-Saxon countries) or public money and it’s the products offered by the bank which make up bank money, that’s to say money directly used by the economic players. This bank money is more or less liquid, depending on whether we are talking about cash in circulation (coins and notes), bank credits, short-term deposits or longer term investments, for example. This bank money is, therefore, the economy’s blood and the bank, by the creation of these financial products and, thanks to the circulating speed of the money produced, functions as a credit multiplier, expressed as the ratio M2/M0 (M3/M0), by monetizing the economy’s assets. Experts in the field have developed quality indicators, with monetary aggregates, allowing the blood’s quality to be gauged, when all is well and stable or, on the contrary, to understand the illness and try remedies when abnormal symptoms appear, to improve the patient’s condition (the economy). So:

- M1 is the most liquid aggregate, consisting of coins and notes in circulation and at bank current account deposits;

- M2 is made up of M1 plus household savings, deposited in and remunerated by savings accounts, term accounts and fixed deposits for less than two years. M2 has a direct impact on the potential for household consumption;

- M3 comprises M2 plus corporate savings this time, still fixed for short periods less than two years. M3 is thus a scorekeeper of liquid asset size, therefore of resilience, and business investment.

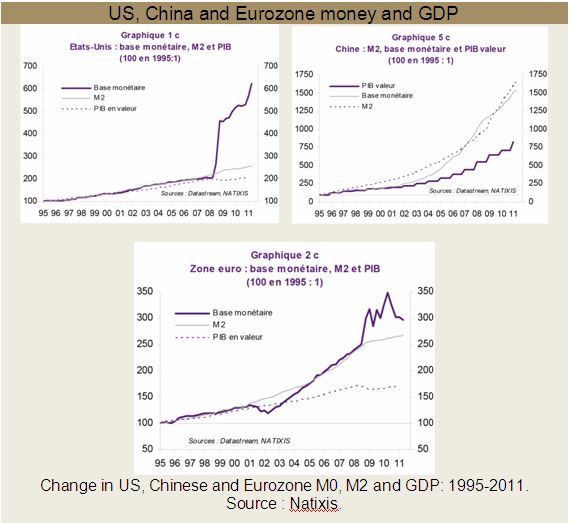

So, it’s very informative to look at inflation’s progress, GDP and money supply, with the base numbers and assets, M2, of the three major economic blocs to visualize these events in action. The multifaceted change is viewed over an expanded time range, from 1995 to 2012, which allows behaviour in normal mode to be seen, from 1995 to 2007, then in crisis mode from 2008 and since the cartloads of public money dumped by the major countries’ central banks.

In the numbers below, the interaction between currencies, M0 and M2 and the economy, is shown for the US, Europe and China. Each chart shows the change in the monetary base, at the central banks’ initiative, then it’s interaction with M2 aggregates, and then on the economic sum total shown by GDP growth. Inflation, which is the other important variable in the system, is of no great significance for this chart, since from the crisis beginning in 2008, it’s around 1% to 2% in the US and Europe, even less, and around 3% to 4% in China, so it can be considered stable. This assumption means that monetary stimulus (less a small stable share due to inflation) should therefore be found in full in GDP growth.

If this were not the case, it’s because the monetary system in place is sick. For example, the stimulus could create inflation without GDP growth, which would be stagflation, as at the beginning of the 80s. But it could also be that it generates neither GDP growth nor inflation and that would then be a sign of deflation that it’s hiding. A very serious deflation, since it’s not responding to the usual treatment which is boosting the monetary base.

One can see in China’s case for example, that the change in the M0 monetary base is really linked to a very dynamic growth in M2 bank money (circulating at high speed since the beginning of the 2000s) and GDP, with moderate inflation (4%-5%). So the system works and is relatively well controlled, albeit with a few anomalies, almost certainly due to the reliability of official statistics (inflation is undoubtedly higher than published data).

In Europe, we can see that the model has stabilized, after initial hesitation related to the creation of the Euro in 1999, but only to 2009. After 2009, we can clearly see that ECB stimuli, with sporadic injections to the monetary base, have led to a moderate effect on M2 growth, tending to invalidate the stimulus strategy to create growth.

But the US example is spectacular and should depress all Western monetarists. First, we see the Fed’s printing multiplying the monetary base by a factor of 3 or 4 since 2008, whilst in Europe this growth is barely in the order of 50% to 60%. Second, it appears that M0 growth was glued to GDP’s at the beginning of the 2000s, so no room for inflation, whilst there was a little. It’s therefore likely that GDP is hiding a false component which bulks it out. Finally and especially, a layman can see that there is no relationship between this exceptional monetary stimulus since 2008 and the change in M2 mass ! It’s difficult to see anything else.

How can such specifics be explained, totally new in modern economic science and finance ? Not only is there deflation but, in addition, this deflation is no longer responding to the sledgehammer approach which would normally neutralize it over several quarters. One rather has the impression of a large sticking plaster on a wooden leg.

In fact, the banks which receive this base money no longer turn it into financial products multiplying credit for the economic players. They themselves are the last economic player, either by repaying their own debt and rebuilding their reserves for example, but especially, because they have changed from a profile of financial service banks to investment banks which by assets directly, rather than generating credit for non-financial corporations (NFCs). They are therefore drying up the flow of available private credit.

Then, this new kind of investor will rush to leave US soil with these free funds to invest in Asia, with a guaranteed, risk-free return of 5% to 6%, whilst in North America the fall in interest rates means that financial investments no longer bring a return. This type of currency peddled by these new players is called hot money[2], which abounds in the financial sphere, totally speculative and irrelevant to the real economy. Once in Asia, these investors buy safe assets (real estate, industry, etc.) and in foreign currency, so as not to lose everything when the Dollar collapses. And it’s the Asian partner, finding itself stuck with Dollars, that it will seek to rid itself of as quickly as possible, like the jack of clubs or spades in a children’s card game. At the end of the game the one who is left with the jack has lost.

Since the 80s-90s this new kind of investor has found friends of fortune on its global path. With the visionary talent of Jack Welch, former chairman and CEO of General Electric, named “Manager of the Century” by Fortune magazine in 1999, the real economy is becoming increasingly financialized and generating global groups with the same profile. Indeed, the largest businesses in the economy, general or multinational, themselves also have a financial department which has a role as hot money investor. Except that this hot money is deducted from subcontractors, such as SMEs, which are only paid 85% or 90% of the contract (because paying a supplier 100% is a management error in modern finance), in 120 rather than 30 days, and after unspeakable administrative and legal intricacies. So, the SME finds itself short of cash, it’s bank won’t lend it anything because it could be at risk and, if things last a little longer with a fall in activity and margins, the SME goes bust. Then, the global business buys it for a pittance and we see a new episode of economic concentration and siphoning of industrial wealth from the bottom to the top, with mass unemployment into the bargain. Therefore, this crisis doesn’t cause damage to everyone, we suspected as such.

Faced with this evidence, we can understand that the Fed doesn’t trumpet loudly and clearly that the world’s primary economy is suffering from a severe deflation. One doesn’t advertise illnesses. But from there, to accuse Euroland of being the only sufferer is a step that global finance communication services blithely cross, as they have already done on the debt, moreover.

So then, what is the Fed, which is necessarily fully aware that QE has had no effect on growth, seeking ? We can rightly imagine that, being aware of the situation’s gravity, it’s showering the major banks (the primary dealers) with readily available public money (base money), so that these dealers by the world’s assets as quickly as possible, because it’s now a race against the clock for the Dollar’s collapse in this mummified economy.

So, should the extreme remedies against deflation in the US be copied 100% by the ECB? The preceding analysis shows that they shouldn’t be. To revive the economy, the true, the only way to create real wealth is by the necessary repair of the credit circuit to the private economic players (private credit), the NFCs, by protecting the SMEs from the hot money predators and probably by developing new arteries for the economy via money and credit. In this perspective, it seems strategic to develop a new path on the banks’ back if we can no longer count on them, or at least fix the profile of these service providers, which won’t be easy. It appears that Mr. Draghi has well understood the problem of the need to play on the flow of credit by providing more base money to those who play that card correctly, but will this traditional method of distribution the effective ? This is what we would like to see, but there is every reason to be very careful. Then next, it will be necessary to rekindle the NFCs’ appetite for credit, therefore clear prospects to restart the machine, because it’s these businesses which create most of the jobs. In the best case scenario the relevant view is over the long term, and after a long convalescence… Subscribe

——————————————————————————–

[1] Artus, P. (2011) Monetary base, money supply and inflation, Flash Economics, Natixis, N° 597 – 10/08/11

[2] (According to Mediadico). Its capital seeking investments for the best short term profitability regardless of the financial market, currency and investment. It’s also called “floating capital”. Speculative capital moving from one place to another, ready to invest short-term, depending on changes in interest rates and the evaluation of exchange rate risk.