Nuclear power and public opinion: a long-standing dislike

Many people deplore (often rightly) the disconnection between political decision-makers and citizens. But when it comes to nuclear power, it is clear that decision-makers resolutely rely on the opinion polls they can find to establish their strategy. To understand this, we need only look at the decline in nuclear capacity worldwide following the Fukushima accident in 2011. Logically, this is most evident in Japan. While nuclear power used to provide about a third of the electricity consumed in Japan, by 2019 it will account for only 7.5%, with only nine reactors still in operation. The impact of the accident was felt in Europe, where the most emblematic reaction was from Germany. Only three months after the disaster, the country decided to phase out nuclear power by 2022. Today, eleven of the seventeen nuclear reactors have been closed for good. Switzerland, Italy and Belgium have had similar reactions. Taken as a whole, the trend is for a decline in nuclear power generation worldwide.[1]

At the same time, there is a desire to develop low-carbon energy, mainly through renewable energies, on a global scale. And this is where we are approaching a paradox that we anticipate will soon be resolved. To understand it, let us take a closer look at public opinion.

As written in the introduction, civil nuclear energy is often perceived as the enfant terrible of military nuclear energy and therefore of the atomic bomb, and rightly so. Firstly because, historically, the nuclear bomb predates the development of nuclear power generation systems. This was the case for the first three countries with a military nuclear arsenal, the USA, the UK and the USSR. The next three countries went in the opposite direction, first developing civilian technology and labelling it as peaceful, before developing their first bomb.[2] This association between the military and the civilian is therefore perfectly logical and is still largely maintained, at least from a Western point of view, by the Iranian issue (if Iran is facing so many difficulties in developing nuclear electricity production, it is because of the fear that it will eventually have a military nuclear arsenal).

Over time, other criticisms have emerged, mainly concerning the safety of the plants and the management of the waste they produce. The question of safety resurfaces, again in a perfectly logical and justified way, with each accident, the two most important being Chernobyl in 1986 and Fukushima in 2011, but we could cite many others such as Three Mile Island in the US in 1979 or Windscale/Sellafield in Great Britain in 1957. The negative impact of these accidents on public opinion towards nuclear energy is clearly visible in the various surveys conducted over the years, although there are significant disparities between countries. Public opinion and its evolution have conditioned the various political choices outlined above. Nevertheless, there are trends that can be seen in the long term through these polls. We base our interpretation on surveys conducted at European and global level around 2010 (i.e., before Fukushima) and 2017, by Eurobarometer,[3] the IAEA, the OECD[4] and ATW[5] (International Journal for Nuclear Power).

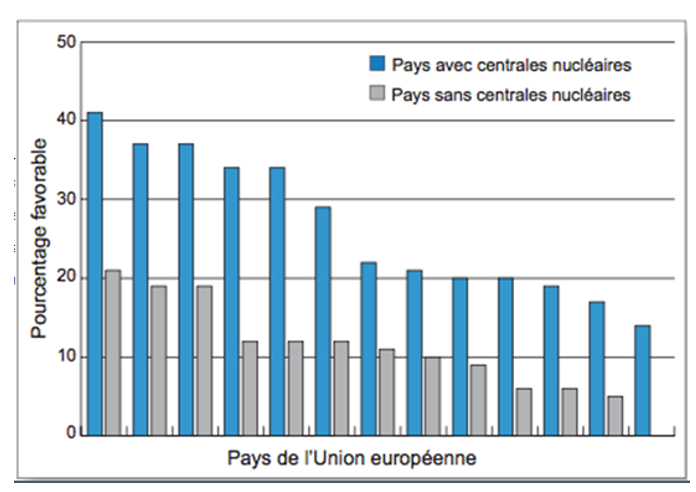

The share of public opinion clearly in favour of developing the civil nuclear industry is in the minority in most of the surveyed countries. The concerns of the respondents are mainly related to safety, waste management but above all to the price of energy, with doubts expressed about the cost-effectiveness of nuclear energy. Among the most interesting points to note, the negative opinion towards nuclear energy is correlated to the knowledge of the issues related to this energy as well as to the presence of nuclear power plants in the country of the survey respondents. Clearly, the more developed the nuclear industry is in a respondent’s country of residence, the better informed they feel about the subject and the more likely they are to have a favourable opinion of the atom. The reverse is also true: the fewer nuclear power plants there are in a country, the less informed the inhabitants feel about the issue, and the more likely they are to have a negative opinion of nuclear power. This trend is even more true in European countries than in the rest of the world.

Fig 1 – Distribution of respondents “clearly in favour” of nuclear power according to the presence or not of a nuclear power plant in their country of residence. Source: OCDE

With regard to climate change, which is a growing concern in European public opinion, there is little recognition that nuclear energy is not a contributor. This situation has been changing in recent years, and a growing proportion of the population considers that nuclear energy should be an important part of the energy mix, alongside renewable energies. Finally, the various surveys consulted all come to the conclusion that countries wishing to promote the development of nuclear energy must rely on better information for the population and a quality public debate. For the concern about energy, and nuclear energy in particular, remains secondary in the minds of those polled, appearing behind issues related to unemployment, safety or health, for example. These are what pollsters call back-of-the-mind concerns, and are therefore easier to change in people’s minds than those that appear to be priorities. On the other hand, as the cases of Finland and the UK demonstrate, an honest and transparent public debate that effectively addresses concerns about nuclear power can result in strong public support for the technology.

It is on this point that we anticipate the future of nuclear energy will be played out, as the next technological advances in this field will provide the governments of the various European countries with elements to fuel a quality public debate dedicated to promoting the development of nuclear energy, which they consider indispensable for serving climate, economic and geopolitical ambitions.

Not a GEAB reader yet ? Register now

[2] Source: The New York Times 05/12/2007

[3] Source: Eurobaromètre, 2010

Comments