GEAB 181

“Be greedy when others are fearful”[1]

The great feature of 2024 is its jam-packed electoral calendar. This year, almost three billion people will be voting in 76 countries, including major ones like India, Indonesia, South Korea, Japan, Russia, South Africa, Algeria, Rwanda and, of course, the United States.

All these countries find themselves in a political stand-by phase during which few decisions will be taken, even if visions of the future will emerge – something to be followed closely. In terms of international relations and diplomacy, it will be difficult to implement strategies in such a context of political uncertainty.

Considerably complicating matters is the fact that the final election in this series, the U.S. presidential election, occurs last. As a result, any potential political changes will be enacted without a clear understanding of the political, economic, and geostrategic directions that the foremost global power might adopt by 2025. Two trends stand out:

. Strategic paralysis, on the one hand: part of the world (particularly the Western world) will go into a “wait-and-see” mode before setting off again with more elements;

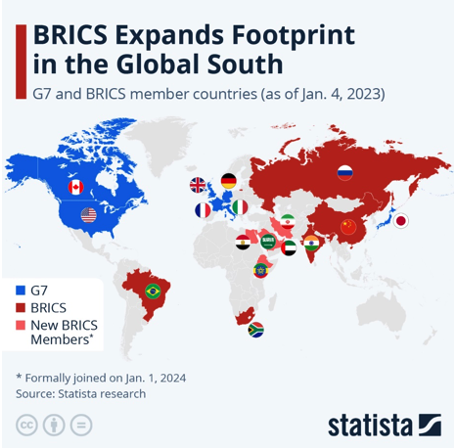

. On the other hand, the United States will be less taken into account: when the other part of the world (BRICS and Global South) will take advantage of this stasis to advance its pawns, without taking into account an America and a Western world that are busy elsewhere.

From a systemic point of view, this dual trend makes it possible to anticipate:

. Major steps forward made by the BRICS, who will be seen as geopolitical players facilitating structural reconfigurations and inventing new methods of global governance;

. A widening gap emerging between leaders and citizens in Western countries, characterised by citizens’ sense of urgency regarding pressing issues, contrasting with the more cautious and wait-and-see approach adopted by leaders.

Hence, the upcoming year in the Western nations is poised to be profoundly political, marked by significant risks of public dissatisfaction. The mitigating factor lies in the potential for democratic expression through elections, albeit only conducted in specific countries and involving a diminishing portion of the population, thus paving the way for the rise of the extreme right.

In contrast, in nations closely tied to the BRICS dynamics, the focus of the year will predominantly be geopolitical. Populations in these regions will likely view promising prospects, leading them to be more lenient towards certain democratic shortcomings. Additionally, it’s worth noting that the Western-style democratic model is no longer an aspirational ideal in this “other world.”

We therefore anticipate a year of geopolitical alerts designed to shake things up, but in a controlled manner. The virulent reactions of the Western camp are bound to frighten us every time. But in the end, we expect more fear than harm in 2024.

Figure 1 – Geographical comparison of G7 versus BRICS+ Source: Statista

Geopolitics: Points of stalemate and resolution

The points of uncertainty are the Ukrainian and Israeli conflicts, which could drag on for another year:

. Israel estimates the chances of resolving the conflict on its terms by 2025 (institutional elimination of Hamas – and probably Hezbollah); a Gaza Strip under Arab trusteeship.

. Russia suggests the possibility of a conflict persisting for another five years, a “threat” that may not warrant excessive concern. This is underscored by the influence exerted by China on Russia. The activation of China or another global player becomes a significant consideration, especially as the United States diverts its attention from the Ukrainian issue. Europe finds itself constrained by the fate of Ukraine, and the resolution of the conflict is anticipated as a trend leading up to the American election, potentially concluding by the end of 2024.

As for the major geopolitical flashpoints:

. Taiwan has just elected a President in the anti-Chinese vein of the outgoing presidency, who will defend the island’s political sovereignty in the face of China’s ambitions, and who must be forced to admit that his role will have to be played differently.

. This is a role offered to it by North Korean provocations, which it has an interest in containing if it wants to take advantage of a stable neighbourhood for flourishing regional trade. China, but also South Korea (helped by a legislative election that will express a desire for national unity[2], reinforced by growing concerns about inter-Korean confrontations[3]) and Japan, will see this as an opportunity to find a lasting solution to this “lock” on peace, one of the first signs of which was the resurrection of the CJK trilateral agreement (China, Japan, South Korea) to end 2023[4].

. Far from rekindling Sunni-Shiite antagonism, the Islamic State’s claim to responsibility for the attack on the Soleïmani tomb brings Iran closer to the regional anti-terrorist plan (remember our long-standing analysis: the Islamic State is the common enemy of the region instead of Israel).

As for the geopolitics of small steps:

. Ethiopia has imposed its access to the sea, and Somalia’s indignation will do nothing to change this; on the other hand, Somaliland, which until now has only been recognised by Taiwan, is gaining international recognition (especially from Africa)[5].

. Azerbaijan and Armenia are on the road to integration of the South Caucasus region – as soon as France stops supplying arms to the Armenians.

. Venezuela is trying to recover 7/10ths of Guyana; if it succeeds, Surinam could try to recover its own claim area; Guyana’s future is therefore at stake; the return of England to the defence of its former colony…

In the realm of global governance, the crucial efforts to reform international institutions such as the United Nations and WTO will continue to falter, contributing to the ongoing discrediting of Western-centric governance as a whole. Simultaneously, newer mechanisms established by the West, notably the G20, remain under the influence of BRICS nations, with Brazil currently holding the presidency and India scheduled for 2023. The BRICS, led by Russia, are poised to advance with relative freedom, leveraging the political inertia in the West and a limited awareness of the growing appeal of the political value proposition offered by the “other side.” This sets the stage for a compelling agenda aimed at bringing about a paradigm shift[6].

Login

Geopolitics: Asymmetrical Recomposition 1 - American election fog disrupts global visibility The fog surrounding the American elections is disrupting global visibility. What will this lack of visibility mean for the [...]

This month we had the pleasure of discussing with Dr. Maria Moloney what 2024 may bring regarding AI and data protection innovation, as well as issues of European and global [...]

Bitcoin: Double-edged institutionalisation The United States' recognition of Bitcoin's legitimacy via the ETFs will be a double-edged sword: it will consolidate the Bitcoin's value and status in the short term; [...]

Comments